|

How is it possible not to feel somewhat in love with spring? A friend says: allergies. Another says: the fickle weather. Another: too much rampaging sap, in humans too, leaving us cranky and exhausted. This year, as I feel the minutes slide through my fingers at a speed I never noticed before, what dampens my love of this season, a season that thrilled me even as a kid, is the understanding that it is a season of loss. We think of autumn that way, with its dying back of life and light, but spring is the season of change, and change—impermanence—is the essence of loss. Every blossom blown by the wind in or out of my yard is a tumble from a kind of biblical grace, a transformation of landscape, a movement along the path to inevitable autumn. I want to stand at the gate and shout, “Slow down! Don’t move! Give that back!” Give me a minute to breathe it all in before it turns into something else.

So the outrageous beauty gets lost under a veil of dissatisfaction, and I look up and wonder where the spring went, how it got away. I’ve learned a trick to capture life before it passes. The trick of writing came to me when I was still a very young kid. I kept a diary, kept it safe with a feeble lock and key, and in it I recorded the day’s events--disgusting fried eggs for breakfast; Miss Allison gives too much homework! Lots of exclamation points and revelations about foods I didn’t like. Then storytelling came to me. Better than the lock and key, it kept brothers out of my business. I disguised everything, absorbed myself in three-line fictions. If a day had gone badly—and they began to when I was twelve—I simply rewrote the events as they should have occurred and felt cleansed of all the messy parts of my personality. I took what had passed and transformed it. Years later, when I no longer needed to do that, I understood the difference between storytelling in order to hide, and fiction as a vehicle for truth. Truth, and by close observation, a means to slow down and savor this life around us and in us, the torture and rapture both. When I write I am never dissatisfied. I am occupied and almost emotionless. The emotion arrives when I am done, like being released from the pull of a powerful eddy. There are times when there is no room for anything but what is right here, and those times are precious, rare. They lend energy and a quality of deep interestingness to everything we are and do. There is no gain or loss, no time or season passing. Complete absorption releases the mind and body. It allows us not to think things through but instead to follow the lead of something that has already arrived at our destination. What we create in those times has a quality of smoothness and ease. A quality of unthought shines through. See if that doesn’t strike you here in a passage from Toni Morrison’s Beloved. I’ve been working at this book for close to a month. I finished it just minutes ago and the passage I wanted to record for its smoothness, truthfulness and ease lands about ten pages from the end. It’s speaking about Paul D’s attempted escapes from slavery to freedom: “And in all those escapes he could not help being astonished by the beauty of this land that was not his. He hid in its breast, fingered its earth for food, clung to its banks to lap water and tried not to love it. On nights when the sky was personal, weak with the weight of its own stars, he made himself not love it. Its graveyards and low-lying rivers. Or just a house—solitary under a chinaberry tree; maybe a mule tethered and the light hitting its hide just so. Anything could stir him and he tried hard not to love it.” Wonderful, isn’t it? A personal sky, weak with the weight of its own stars? I can feel that. And even if you’ve never seen a certain light hitting a certain mule, you can picture it. There it is, right in front of you, smooth and easy. And that chinaberry tree? I have chinaberries in my own yard. They blossom early, the palest pink. They send out the first invitation to sink into the temporary glory or shield myself with dissatisfaction. This season, which will it be? How hard will I try not to love it?

2 Comments

Walt has called upon his three good friends to make him a coffin. “I’ve never died before,” he says. “I’m not sure how to do it. But I’ll need a coffin.”

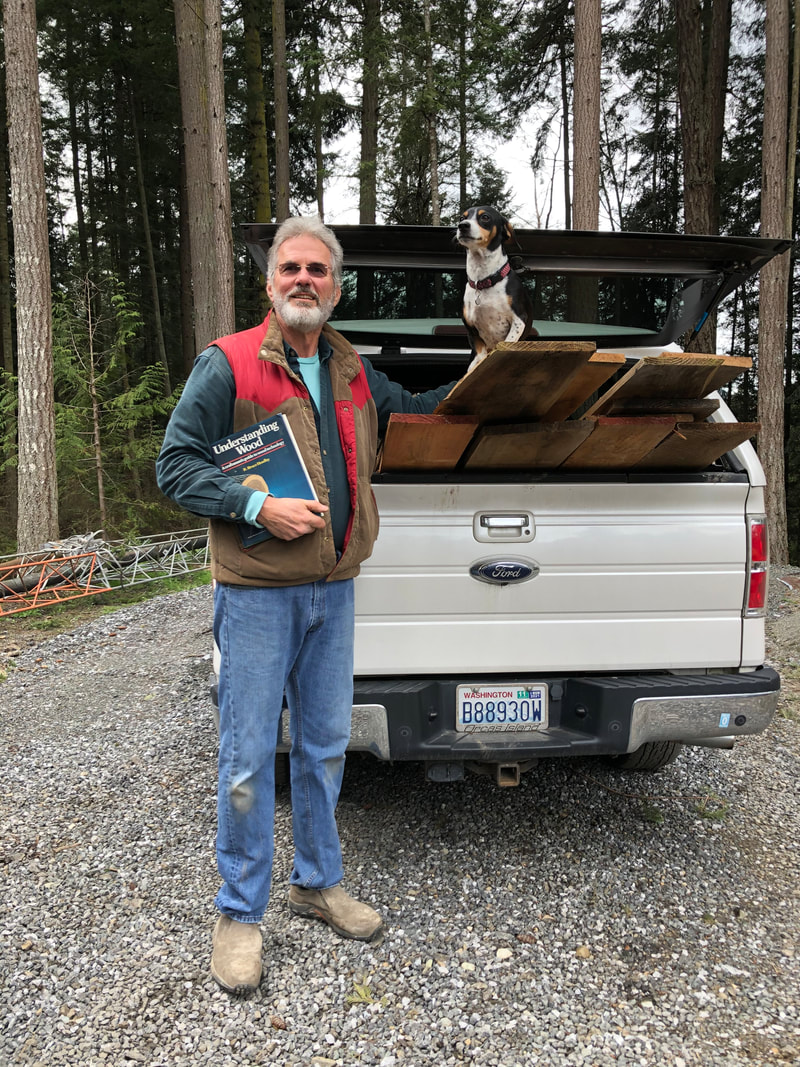

The four good friends go together to Walt’s woodshop to pick out the boards. They’re looking for cedar, and as they search through the lumber Walt reminds them they don’t need to nail or peg or screw the coffin together, they can just use glue. One of the good friends, Mark, doesn’t like that idea. It’s practical, he says, but a coffin isn’t about being practical, it’s about respect. It’s about being respectful and giving someone a good-looking send-off, the one they deserve. A sweet-smelling send-off, says Joe, pressing his nose to the cedar. Otherwise, says Andrew, we’d just wrap you up in a sheet. They find the boards they want and load them into the truck. Mark’s dog Spud, part beagle, part dachshund, part whirling dervish, stands up tall in the back. Time for a lie-down, says Walt, and off they go, dog ears flapping in the wind. I wasn’t part of this story. I was only the ears to hear it. But who can’t picture it? The four friends, Walt, Mark, Joe and Andrew, enacting the rituals of friendship, so close to kinship at times. When there are tasks to do, they do them. When there are feelings to express, they find their way to them. Kindness isn’t a word they’re comfortable with, but they know about giving. I picture Mark planing the wood for his friend’s last enclosure. He’s old-school and he’ll use pegs and Walt will be pleased with the look of that. Though suddenly he wonders if his friend will come and see the coffin before he’s placed inside it. Maybe it’s bad luck, he thinks. Maybe it’s not so different than the wedding-day custom of not seeing your bride, not until you lift her veil at the altar. That always seemed silly, old-fashioned. Did anyone do that anymore? But coffins are old-fashioned. They have six sides, they’re not easy to make. A casket only has four. No one even says the word “coffin” in these modern times. It’s a word that frightens people, it reminds them of death. Yet it means “little basket.” Mark likes that. He’s making Walt’s little basket. Walt is losing a pound a day and suddenly Mark wonders if he should go and measure him. He doesn’t want the coffin to make his friend look small or insubstantial. He planes away, thinking about Walt and the fish they’ve chased and sometimes caught, and their mutual love of boats and, he’d have to say, yes, wood. The grain of the wood. And especially this wood. It curls away beneath his hands and he thinks again of all he doesn’t know about the customs of death, and how he, like Walt, doesn’t know how to do his own dying. But he’s learning. With every sweep of the plane, he’s learning. They’re all learning, and right now, because Walt’s going first, they’re learning from Walt. |

AboutA place to discuss writing or anything on your mind. All visitors are invited to join the conversation by commenting on posts, asking questions, and joining the newsletter below for even more opportunities to connect and converse! Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed