|

But for the pungent dog poop that lay in a frozen state all winter and came alive as the sidewalks heated up, May was a glorious time in New York City. It was my favorite month of school because we spent so little of it at school. There was Field Day, an entire day when we got to run around like hooligans on Randalls Island, hurling softballs at one another and competing in the 100-yard dash. There were class trips to the Cloisters, to the hall of mummies at the Metropolitan Museum. But as memorable as those were, nothing measured up to the trip to one of the more unlikely places in Manhattan. This was a place intended to ignite a spark of what? passion for learning? in a gang of chattering first-graders? What mortal minds concocted such a plan, I’ll never know, but 62 years later, while I can’t remember the name of the woman next door who likes the same music I do, I clearly remember that day at the Fulton Fish Market.

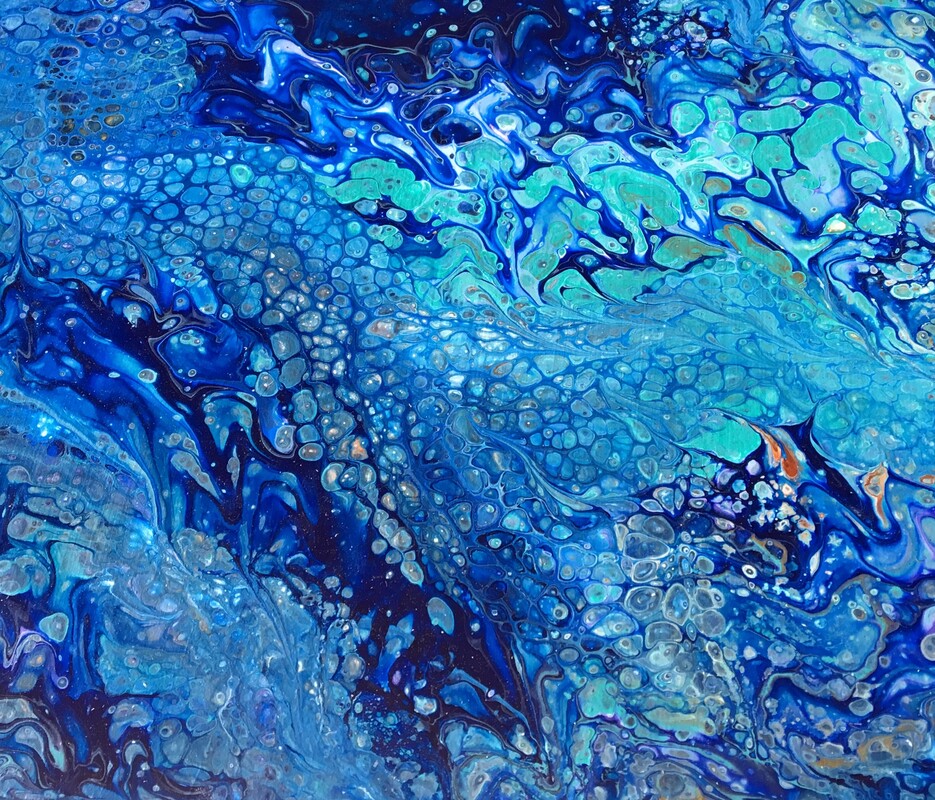

In their own words: Opened in 1822, New York City’s Fulton Fish Market is one of the oldest fish markets in the United States. Well before the Brooklyn Bridge was even built, the market at South Street Seaport thrived with fishing boats and fishmongers bartering and bantering over stalls heaving with fresh fish. Each night the colorful market would come to life with its cast of characters, eager chefs and curious tourists, all mingling over bushels of oysters, crates of lobsters and a kaleidoscope of sea creatures from near and far. Perhaps more than any other institution, the Fulton Fish Market captured the spirit and tradition of old New York. I feel a warmth around my heart just reading that paragraph. Stalls heaving with fresh fish. Fishmongers bartering and bantering. Something in my body remembers the temperature of that day, the smelly warmth of the market, the cool of the ice, the noise, the hawking, the very New York entrepreneurial buzz, the accents and flavors of the city, all overwhelming to an Uptown kid in a blue school uniform. I remember the ordinary fish I carried home on the school bus in a neat white package and delivered to my mother. I remember her expression as she thanked me. It was the look of someone who loved me and understood the importance of the gift, never mind that the fish and its ice had parted long hours before. Was this the lesson, where my mother’s love and an overripe fish came together to create in me a thirst for the world? Or was it the passion of the fishmongers, the shouting and colorful tangle of the senses that let me know learning was limitless, that it took every form imaginable? When Shakespeare came along, I could picture Capulets and Montagues duking it out at the Fulton Fish Market, and the fair Cordelia leaning over a basket of raw shrimp. When Brutus stabbed Julius Caesar, he did so not in the Curia of Pompey, but in the Fulton Fish Market. With my own eyes I’d seen the stain of the emperor’s blood on the ground between a case of red snapper and the lobster pool. When Pythagoras offered up his theorem, the hypotenuse was always the Brooklyn Bridge hanging over the East River that day at the market. And when we studied the Revolutionary War, the fishmongers were the ones who showed up with ice picks and gutting knives to turn back the British at the mouth of New York harbor. Make no mistake, George Washington’s private militia was made up of these men, these ordinary bantering bartering men in blood-stained aprons and high rubber boots. These men who could set your imagination on fire. These men who could sell you a fish.

0 Comments

We are recognizable by our green hair and wandering tan lines, by our distinctive odor nicknamed eau de chlorine. Without our daily fix we are crazed. Our hands shake, our knees jiggle. We are swimming pool junkies waiting for lap hours.

We’ve seen it all—fistfights and shouting matches in crowded lanes where circle swimming is required. Someone in the intermediate area is sent back to the slow lane. Or there’s a thrasher, a guy who hasn’t yet mastered the strokes, and if you pair with him in his lane he’s apt to whack you on the head. Or jab you with his foot. He’s all over the map and that violates the unspoken rules of the natatorium. Swimmers like tidiness, efficiency. That’s why we commit the sporty hours of our lives to the fixed geometry of lap lanes. We immerse ourselves in the rectangular waters of a pool. We follow a fixed line on the pool’s silky bottom. We sandwich ourselves between plastic buoys that keep us in our own world, far from the business of everyone else, and there we finally relax and just swim. I learned to swim in my grandmother’s pool in New Jersey. Summers in the Garden State were so hot our bodies literally ached for water, and there it was every morning, that beautiful cool blue rectangle of chlorine, awaiting our joyful whoops and cannonballs and ichthyic underwater acrobatics. We were tadpoles one minute and frogs the next. We were whales breaching, flounder flapping along the rough pool bottom. Our hair was green, our sunburned skin turned from red to brown. When we reluctantly stepped out of the pool at the end of the day the water flew off us in scintillating drops. We looked like we were shedding diamonds. I didn’t swim again, not with the same passion and attention I had as a kid, until I found myself in Arizona in the mid-seventies. Maybe it was the unfamiliar waterlessness of the Southwest that made my body thirst for a pool. Maybe it was my friend Lew’s suggestion that I count the laps, 36 to a mile. Once I got going there was no stopping me. I swam in Prescott and Camp Verde. I swam in Cottonwood in an ancient trapezoidal pool that had the effect of merging traffic in the shallow end. Bodies bumped against one another and jostled for room to do flip turns. It went against all swimming etiquette but was, in fact, a pleasant meeting of underwater skin. I made a point of visiting places known for their pools. I took to the water in Hemingway’s chilly outdoor pool in Key West; the YWCA’s clothing optional pool in Cambridge, Massachusetts; a pool in an abandoned convent in Santa Barbara, with a pool deck tiled like the Baths of Caracalla. I swam alone in an Olympic-size pool north of Bangkok, and a frog-filled pool in Mandalay. At a Zen monastery in California’s Ventana Wilderness, I swam daily in a pool warmed by hot springs. Later I became the keeper of that pool, the skimmer of leaves, rescuer of bees. Ocean swims, lake swims, river swims. These are all acceptable to swimming pool junkies but they’re not the glory we live for. Oh, those traversers of the English Channel, the Bering Strait. What strange compulsion drives them to such uncomfortable extremes? The terrible cold, the energy delivered through a feeding tube, the lonely vigil in the dark, the terror of traffic in the shipping lanes, the absence of direction out there in the vast beyond. They move between countries, continents, with the same strokes that deliver me to the far side of the pool. What different destinations! What unimaginable desires! Only once did I sign on to an ocean swim, an event to raise money during the AIDS epidemic. Our course wasn’t long, a mile-and-a-half, but it was mid-September and the water was chilly. I was one mile in, my core noticeably cooling, when I heard the scream of another swimmer. She was slightly behind me when she yelled, Shark! I turned and there was the unmistakable fin circling her. It was, I later learned, a harmless species called a nurse shark. Still, that put an end to my ocean distance swimming. In lakes and rivers I’m similarly afraid a fish will brush my leg. But in the pool, antiseptic and chlorinated, chemicalized to an otherworldly hue, the monsters of the deep exist only within me, and that’s what I’m there for. I swim to shake them off. Impossibly, one Christmas my mother gave me a raccoon coat. It was not a new coat, but neither was it the worse for wear. The fur, or pelt might be a more accurate word, was not moth-eaten or sorry looking, if a bit dull, and my mother had replaced the entire lining with the same brilliant blue fabric that covered our living room chairs. She had rebuilt the coat from the inside and she presented it to me that Christmas, the Christmas I was twelve, with a beam of pride that broke my heart. Because the last thing in the world I wanted was to walk out into the jungle of New York City and through the doors of my school wearing a bunch of dead animals on my body. The last thing I wanted was a raccoon coat.

I thanked my mother profusely, overdoing it to cover my shame. It was the shame of ingratitude, the anticipatory shame of arriving as I must in front of 610 East 83rd Street, my school, and being the laughing stock, the butt of the joke, the blushing target of everyone’s unmerciful teasing. Juanita Dugdale had worn a modest fur hat to school one day and for that she was crucified. I knew the consequences and my mother did not. Her plan was to save me in style in those cold New York winters but in fact she was throwing me to the wolves. My older sister’s best friend Kate was the first to land a dart. She looked me up and down and smiled dangerously as we stood at the bus stop together. “Height of prep,” was all she said. I remember the sting of it to this day. But I was grateful for the efficiency, the brevity of her blow. Others were not so reserved, or rather not so accurate in the delivery of their poison arrows, and several seemed genuinely confused as to whether or not the coat was made from our own pet raccoon, Mr. Peepers, who had come and gone in our lives several years before. I came home from school and stood as I always did in front of the cracker and potato chip closet above the built-in oven in our kitchen, and cried. I had not even bothered to take off the coat and I stood and hung my head and blubbered into the scratchy fur that came up to meet my face. Here it was, this hideous coat with its beautiful, elegant, blue as the blue sky lining, hand-sewn by my beautiful, elegant mother, and I had to choose. I had to either bear the shame or refuse the gift which at that moment felt like refusing the gift of life which she had also given me. With all its difficulties and uglinesses I hadn’t refused that gift, had I? the gift of life? It was difficult and complicated, even hideous at times, but I had chosen to concentrate on life’s beautiful blue lining and now, I decided right there in the kitchen, I would do that again. How is it possible not to feel somewhat in love with spring? A friend says: allergies. Another says: the fickle weather. Another: too much rampaging sap, in humans too, leaving us cranky and exhausted. This year, as I feel the minutes slide through my fingers at a speed I never noticed before, what dampens my love of this season, a season that thrilled me even as a kid, is the understanding that it is a season of loss. We think of autumn that way, with its dying back of life and light, but spring is the season of change, and change—impermanence—is the essence of loss. Every blossom blown by the wind in or out of my yard is a tumble from a kind of biblical grace, a transformation of landscape, a movement along the path to inevitable autumn. I want to stand at the gate and shout, “Slow down! Don’t move! Give that back!” Give me a minute to breathe it all in before it turns into something else.

So the outrageous beauty gets lost under a veil of dissatisfaction, and I look up and wonder where the spring went, how it got away. I’ve learned a trick to capture life before it passes. The trick of writing came to me when I was still a very young kid. I kept a diary, kept it safe with a feeble lock and key, and in it I recorded the day’s events--disgusting fried eggs for breakfast; Miss Allison gives too much homework! Lots of exclamation points and revelations about foods I didn’t like. Then storytelling came to me. Better than the lock and key, it kept brothers out of my business. I disguised everything, absorbed myself in three-line fictions. If a day had gone badly—and they began to when I was twelve—I simply rewrote the events as they should have occurred and felt cleansed of all the messy parts of my personality. I took what had passed and transformed it. Years later, when I no longer needed to do that, I understood the difference between storytelling in order to hide, and fiction as a vehicle for truth. Truth, and by close observation, a means to slow down and savor this life around us and in us, the torture and rapture both. When I write I am never dissatisfied. I am occupied and almost emotionless. The emotion arrives when I am done, like being released from the pull of a powerful eddy. There are times when there is no room for anything but what is right here, and those times are precious, rare. They lend energy and a quality of deep interestingness to everything we are and do. There is no gain or loss, no time or season passing. Complete absorption releases the mind and body. It allows us not to think things through but instead to follow the lead of something that has already arrived at our destination. What we create in those times has a quality of smoothness and ease. A quality of unthought shines through. See if that doesn’t strike you here in a passage from Toni Morrison’s Beloved. I’ve been working at this book for close to a month. I finished it just minutes ago and the passage I wanted to record for its smoothness, truthfulness and ease lands about ten pages from the end. It’s speaking about Paul D’s attempted escapes from slavery to freedom: “And in all those escapes he could not help being astonished by the beauty of this land that was not his. He hid in its breast, fingered its earth for food, clung to its banks to lap water and tried not to love it. On nights when the sky was personal, weak with the weight of its own stars, he made himself not love it. Its graveyards and low-lying rivers. Or just a house—solitary under a chinaberry tree; maybe a mule tethered and the light hitting its hide just so. Anything could stir him and he tried hard not to love it.” Wonderful, isn’t it? A personal sky, weak with the weight of its own stars? I can feel that. And even if you’ve never seen a certain light hitting a certain mule, you can picture it. There it is, right in front of you, smooth and easy. And that chinaberry tree? I have chinaberries in my own yard. They blossom early, the palest pink. They send out the first invitation to sink into the temporary glory or shield myself with dissatisfaction. This season, which will it be? How hard will I try not to love it? Walt has called upon his three good friends to make him a coffin. “I’ve never died before,” he says. “I’m not sure how to do it. But I’ll need a coffin.”

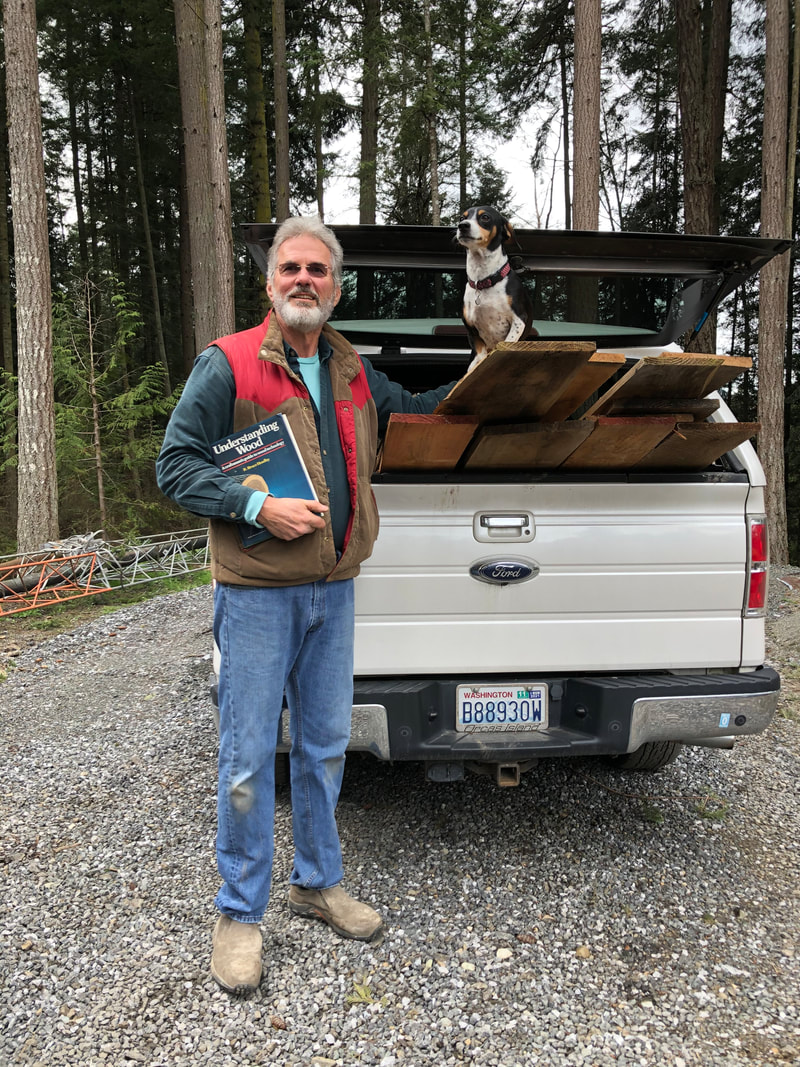

The four good friends go together to Walt’s woodshop to pick out the boards. They’re looking for cedar, and as they search through the lumber Walt reminds them they don’t need to nail or peg or screw the coffin together, they can just use glue. One of the good friends, Mark, doesn’t like that idea. It’s practical, he says, but a coffin isn’t about being practical, it’s about respect. It’s about being respectful and giving someone a good-looking send-off, the one they deserve. A sweet-smelling send-off, says Joe, pressing his nose to the cedar. Otherwise, says Andrew, we’d just wrap you up in a sheet. They find the boards they want and load them into the truck. Mark’s dog Spud, part beagle, part dachshund, part whirling dervish, stands up tall in the back. Time for a lie-down, says Walt, and off they go, dog ears flapping in the wind. I wasn’t part of this story. I was only the ears to hear it. But who can’t picture it? The four friends, Walt, Mark, Joe and Andrew, enacting the rituals of friendship, so close to kinship at times. When there are tasks to do, they do them. When there are feelings to express, they find their way to them. Kindness isn’t a word they’re comfortable with, but they know about giving. I picture Mark planing the wood for his friend’s last enclosure. He’s old-school and he’ll use pegs and Walt will be pleased with the look of that. Though suddenly he wonders if his friend will come and see the coffin before he’s placed inside it. Maybe it’s bad luck, he thinks. Maybe it’s not so different than the wedding-day custom of not seeing your bride, not until you lift her veil at the altar. That always seemed silly, old-fashioned. Did anyone do that anymore? But coffins are old-fashioned. They have six sides, they’re not easy to make. A casket only has four. No one even says the word “coffin” in these modern times. It’s a word that frightens people, it reminds them of death. Yet it means “little basket.” Mark likes that. He’s making Walt’s little basket. Walt is losing a pound a day and suddenly Mark wonders if he should go and measure him. He doesn’t want the coffin to make his friend look small or insubstantial. He planes away, thinking about Walt and the fish they’ve chased and sometimes caught, and their mutual love of boats and, he’d have to say, yes, wood. The grain of the wood. And especially this wood. It curls away beneath his hands and he thinks again of all he doesn’t know about the customs of death, and how he, like Walt, doesn’t know how to do his own dying. But he’s learning. With every sweep of the plane, he’s learning. They’re all learning, and right now, because Walt’s going first, they’re learning from Walt. When people die, especially when they die public deaths, we offer flowers. First Atlanta, then six days later, Boulder. Who will be next? Who have we already forgotten?

The tulips arrived at my house in late February and offered me a chance to remember how we bud, blossom, and die. The brevity of their lifespan gave me a great opportunity, a chance to see and feel the brevity that defines us all. I dedicate the tulip series to those whose lives were months, years and decades cut short by a gun. There’s no other way to say it. I’m tired of removing the gun from the equation. Without the gun, with a knife, say, or a sword, or the bare hands of any confused, deluded, lost or mentally ill someone, the odds would be different. The cards wouldn’t be stacked against a young couple shopping for the perfect lemon in the produce aisle of the grocery store. Come on. “It’s easier to buy a gun in this state than it is to vote.” Chilling words from a Colorado man who witnessed last Monday’s massacre. And that’s another thing. Let’s not call these shootings anything less. The definition of a massacre is the indiscriminate and brutal slaughter of people. All week I’ve waited for the petals to fall. I anticipate they’ll make a pleasing pattern around the base of the vase. But this can’t wait. Not a day longer. It’s time to offer them. The flower heads are heavy, the stems are weak. They appear to be praying. From the pen of the great scholar, Edith Hamilton:

“The Greeks were not the victims of depression. Greek literature is not done in gray or with a low palette. It is all black and shining white or black and scarlet and gold. The Greeks were keenly aware, terribly aware, of life’s uncertainty and the imminence of death. Over and over again, they emphasize the brevity and the failure of all human endeavor, the swift passing of all that is beautiful and joyful. . . . But never, not in their darkest moments, do they lose their taste for life. It is always a wonder and a delight, the world a place of beauty, and they themselves rejoicing to be alive in it.” Oh, Edith, Edith, Edith. This has not been a Greek week for me. I’ll admit I have somewhat lost my ability to rejoice. I am living inside a snow globe, a paperweight that unleashes a blizzard when shaken, and though I am contemplating the swift passing of all that is beautiful and joyful, such as this endless snow, it doesn’t pass. It snows and snows. I should be rejoicing with the words, “Precipitation! Moisture at last!” Instead, I am feeling like a damp shut-in. I swore like a sailor yesterday at someone driving too fast down the street. My anger shocks me. I’m angry, Edith! The transient things seem less transient than they should be. Even the anger gets stuck in my throat—until I curse at a passing car. Ridiculous! The whole show feels like it’s come to a halt. Or rather the parts of the show I’m tired of have slowed to a molassesine pace. I feel trapped in a room with a third-rate lecturer who drones on and on. Wonder and delight you say? Show me such things. And allow me to see them once they are shown. Meanwhile, it’s gray. And I’m one of the very lucky ones with a roof over my head, plenty of food, enough money, and no immediate friends or relatives dead to Covid. And thanks to masks, it’s been a surprisingly healthy year for me. Yet I’m not rejoicing to be alive in this world of beauty, wonder and delight. Ease and luck are mine, yet I shout curses at a car full of kids who are just bored and need a laugh and hey, here’s a puddle of slush, what do you say we speed through it and send up a wicked spray to soak the trousers of the old people out for a walk. Edith. Miss Hamilton. I’ve read your book, Mythology, and when I was young I even modeled myself after Pygmalion, strange to say. Your words, your stories, set a spark to my imagination. You are a scholar who knows how to tell a good story, a great story, especially when the raw materials are so rich, the colors so black, so scarlet, so gold. You were an educator your entire life, and had this to say: “It has always seemed strange to me that in our endless discussions about education so little stress is laid on the pleasure of becoming an educated person, the enormous interest it adds to life. To be able to be caught up into the world of thought—that is to be educated.” I’m at home, looking out at the weather, waiting for the world to educate me—to bring me pleasure—and it isn’t working. I’m tired of myself. My thoughts bore me and I can’t muster my own resources. I feel a little crazy and on the edge of a slippery depression. I’m at sea. I feel without a purpose. Our president keeps advising us to maintain a sense of purpose, or if none is at hand, find one. I notice how hard he works and I have a sudden urge to help him. To leave my home and do something to help. I’m especially touched that in order to hear from people, from Americans, he goes to the hardware store. Our president stands in the aisle in front of the ant spray and garden trowels and has a conversation. I wonder if I could do that here, to find out more about the people with whom I share this town and this earth. This earth and this planet. It helps to get out, Edith. Because everything we do is something done. Every brief endeavor lifts us into purpose, no matter how swift its passing. This has not been a Greek week, but my sights are now set on the week to come. Thank you for your encouraging words. At Green Dragon Temple in California, I met a man whose dharma name I can’t remember and whose given and family name I never knew. He was English and had grown up poor and scrappy. He had only four teeth in his mouth but as he said, he made good use of them. He and I got on like a house afire, for whatever strange subterranean reason people with different habits of humor and dentistry get along. I had the better teeth and he the better sense of irony. He taught me to curse like an Englishman, but in my well-denticulated mouth the words lost their cutting edge and left us both laughing.

His signature expression in any moment of frustration was: Jesus wept. You or I might have said, “Oh, for God’s sake,” but for him it was a headshake and a loud “Jesus wept,” with the “Jesus” drawn out on the first syllable so it sounded like “Jeeeeeeeesus wept.” For weeks I found this expression puzzling. As an expression of frustration it is puzzling. But what made it more puzzling to me was a slight mis-hearing of it. I was certain he was announcing that Jesus swept. Well, he grew up in a carpenter’s shop, I thought. Lots of sweeping. But what does that have to do with how difficult it was to get the old temple truck’s engine to turn over, or to wrestle with the plumbing in the student bathroom in Cloud Hall? Sweeping is a Zen thing, engaged in by everyone—students, priests, abbots—with no questions asked. “Chop wood, carry water” is the practical expression of human life, and life at Green Dragon Temple involved plenty of that for those of us who lived there, whether for a week or a lifetime. Work is an important teacher in the Zen school, and a Zen student’s life is made up largely of meditation and work. Study is important, but getting out of the head and into the body, then beyond the body is the practice. “To study the way is to study the self,” said Zen master Dogen, “and to study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be actualized by myriad things. When actualized by myriad things, your body and mind as well as the bodies and minds of others drop away.” He said more, much more, volumes more, and the myriad things is still a mystery to me, but my own understanding of meditation is that by following the breath as it goes in and out of the body, the mind is freed, not dwelling on anything, just as the breath does not stay still or stuck in one place. So sweep we did, much of the day at Green Dragon Temple. There was always something somewhere to sweep. One day I convinced my English friend that the roofs needed sweeping. The pine needles and leaves lay thick on the temple grounds and the many roofs of the temple buildings were covered with them as well. We rigged a rope and up I went, while he held the other end of it down on terra firma. He was deaf as a white mouse and every time I moved out of sight I heard a long loud “Jeeeeeesus wept” and a tug on the line just to make sure I was still there. It was a glorious day, the sun shining out of the fog and the weedy, salty smell of the ocean coming up from Muir Beach. I was happy sweeping the rooftops and he seemed content holding the rope. He was a cynical man much of the time, but he had a heart capable of melting. I knew he had children and grandchildren, perhaps a wife. In temple life we knew very few details about one another and it didn’t matter. He and I were connected that day. That stout line of hemp held us together. But also the physical activity of making things right, of working, of sweeping, allowed us to leave our minds behind in a kind of self-forgetting. I wondered if Jesus actually swept, and I thought he might have, given as he was to finding a path to the ineffable regions of the spirit, sometimes called God. In June of 1994 I narrowly escaped becoming a wife. Wifedom was not the problem. If a fight breaks out on a bus, is the bus the problem? No. Even if the argument involves some value judgment of the vehicle—“This bus stinks.” “No it doesn’t.” “It’s dirty.” “It’s cleaner than your mouth.”—the vehicle is simply the means of expression for the frustration, anger and misunderstanding that occurs between human beings.

And so it was with our near-marriage. Neither of us was an adequate communicator, at least not adequate to the situation. We had stumbled into relationship a few years earlier and had enjoyed a long peaceful spell, unlike the drama and fireworks of other relationships we had negotiated. That seemed a pattern for a good marriage, and on the second request I said yes. I remember it well. I had spent the morning at the MOMA in New York City, and found a little church to sit in on my way uptown. It was a shadowy place, with smelly Catholic incense leaking from the walls and a life-size crucifix above the altar. Several mumbling people sat in the pews. I slid into the empty back row. I didn’t mumble, but my thoughts weren’t organized or calm. I started noticing things, sensory things. A little daylight squeezed in through a couple of high, stained glass windows and that seemed hopeful. The floor was linoleum, and I kept thinking how I hated the feel of linoleum underfoot on a cold winter day. But it was spring. It was one of those warm spring New York days when the leaves are emerging and the whole city smells of…well, to be honest, exhaust and dogshit. On my way out of the church I thanked it, I thanked the building though I wasn’t sure why. I felt almost as if the church itself had decided to marry, relieving me of that burden and decision. So we almost did. Her religious affiliation was with the Quakers, who threw themselves into prayer and debate and finally, a year later, reached consensus around witnessing our marriage. Perhaps it was just too long to wait for affirmation, an affirmation given to more traditional couples without any such scrutiny. Yet I was impressed by the scrutiny. At the end of that year I felt I had left the scrutiny to others and done too little of it myself. I was vaguely aware that this marriage had become not just a test case for others, but a political sticking point for me. It had become an activist’s weapon, and lost its meaning as a marriage, as a commitment to another, as an act of love. We invited about thirty friends and family. Everyone was asked to bring a pie. A seamstress friend of mine made me a purple wedding frock. Two weeks before the wedding I called it off. The truth is, and the reason for telling this story now is to practice telling the truth, especially the hardest truths, some of which carry shame and all of which carry the knowledge of having done harm—the truth is that in my confusion and continued uncertainty about something called love, I glanced elsewhere and became attracted to someone else. That is the situation my not-wife and I were inadequately prepared for. We lacked the ability to sort out what was reactive and what was not, and whether, as a couple, we were actually suited to one another, and whether marriage was still the best way forward for us. We weren’t actually suited to one another, but a clumsy and unconscious unveiling of this was not helpful or necessary. It was hurtful. It caused harm to everyone involved. There. I’ve said it. And one more thing. While I regret that my not-wife was unable to forgive me, this has taught me that forgiveness, which is a word we use too often as a shallow platitude, isn’t for someone else to grant. Real, felt forgiveness has its source inside. To my surprise, because I’m still a clumsy animal prone to surprises, forgiveness of self and others is activated by truth-telling. I’ve wanted and feared to tell the regretful piece of this story, the shameful, guilt-ridden piece, for a long time. I broke the marriage. By my own actions I caused a great deal of harm. We have that before us now. Now go on. Someone receives a midnight phone call. There’s static on the line. The message isn’t entirely clear. A location is mentioned, then another. A name is given. Then the muffled words “the goods.”

It sounds like a scene from The Godfather, but it’s happening right here in our town. We’re off to another day of vaccinarama, the continuing roll-of-the-dice-rollout that drives the good citizens of Arizona to intrigue in order to secure themselves an inoculation. Listen, as the medical worker who jabbed my arm said, “Consider yourself a lottery winner just to be here,” and I do. I consider myself one lucky duck to have glanced at my email at just the right moment in time to snag a place in line. That day outside the Elks Lodge, it looked like the crowd had arrived for the Flagstaff Folk Festival, eight months late or four months early. We were there to hear the songs of our youth played over and over again, live and local. But instead, it was vaccination day, and the smiles were radiant, the relief palpable. We queued up for forty minutes and longed for the live band, or even the piped-in music, but maybe by the time we head out for our second shot a quartet will be playing under the elk heads. One of my early memories is standing beside my mother and watching our family doctor uncork a little vial of clear liquid intended for me. He probably didn’t hand it to me with the words, “Bottoms up!” but still, there was a festive, let’s-make-a-toast mood in his office. The drink was syrupy sweet and not to my liking, but it would save me from something called polio, I was told. I was too young to know anything or think much about polio. Or smallpox, for which I was vaccinated in a signature speckled pattern on my upper right arm. In grade school, when a classmate fell ill with measles, mumps or chickenpox, and later German measles, we were sent to stand beside her and breathe in her germs and come down with these diseases ourselves in order to “get them over with.” It was awkward to arrive at the house of a girl I didn’t really know, enter her bedroom and sit close to her on an uncomfortable chair and come up with news from school. “Oh, the rabbit got out,” I remember telling one patient who just looked at me and sighed feverishly. Yet I left with what I was supposed to leave with every time, and put the childhood diseases behind me so they wouldn’t come back to threaten my life as an adult. We never thought there was much danger of that anyway, until we almost lost our friend Patrick. Patrick worked in Chad for a humanitarian organization. His young daughter, Ellie, came down with chickenpox and recovered easily but not without first passing on the disease to her father. He contracted chickenpox in his lungs and, close to death, was airlifted out of Africa and back to his home country of England. After some time in Intensive Care he recovered, and was able to return to Chad, but his proximity to death was sobering for all of us, and a necessary reminder of our great good fortune as beneficiaries of medical interventions, magic potions, syrupy sweet liquids and shots in the arm that saved us from crippling diseases and early deaths. The little glass vial of the polio vaccine was a precious, life-giving elixir. I was too young to know it, but I’m old enough to know now that a long line of sixty-fives and older, standing outside in the sun, shuffling slowly forward, happy to be there, excited to see one another out in the light of day—it’s a reminder that to be able to choose this way of keeping life close, of choosing life in this way, is a choice that belongs to everyone. This is a case, not the first nor the last, when what you do affects what I do, when my winning lottery ticket is worth less without yours. The intrigue, the crapshoot as I’ve been heard to call it, will level out here in the great state of Arizona, I hope, especially as more vaccine becomes available. But if we’re wondering how to do this thing, this thing we’ve never done before, a good first step might be to look around at the places where the rollout is working well, like our neighbor, New Mexico. The Grand Canyon state shares a long dusty border with the Land of Enchantment. Can’t we teach each other something? |

AboutA place to discuss writing or anything on your mind. All visitors are invited to join the conversation by commenting on posts, asking questions, and joining the newsletter below for even more opportunities to connect and converse! Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed